Written by Clayton Ilolahia

The emergence of perfumery as we know it today happened at the end of the 19th century. The Industrial Revolution gave fragrance an unprecedented platform across Europe and Great Britain where perfumery moved away from the small laboratories of organic chemists and into factories where large-scale production became the norm. Advances in chemistry enriched the perfumer’s palette with new ingredients and more efficient modes of travel opened trade routes. Western perfumery benefited with increased access to natural ingredients from the East, such as spices, sandalwood, vetiver and patchouli.

At the time sandalwood was already being used in Western perfumery. The high cost then as it is now meant sandalwood oil was reserved for the most luxurious fragrances. Sandalwood’s unique scent and its ability to transform a fragrance has always been revered. As fragrance experts Tania Sanchez and Luca Turin point out in their perfume guide1, “Anyone who has ever worn real Indian sandalwood oil straight knows that it is the perfume in itself: milky, rosy, ambery, woody, green, marvellous.”

The origin of sandalwood was exotic for Westerners at that time. Perfumes steeped in the oil were often accompanied by stories that stimulated the imagination with tales of faraway lands and cultures. Historic British perfume house Penhaligon’s launched Hammam Bouquet in 1872. It remains in production as one of the house’s heritage scents, today described as “the luxurious scent of a bygone era.”2 For it, William Henry Penhaligon paired sandalwood oil with aromatic lavender and Turkish rose oil to evoke the experience of Mayfair’s Turkish baths.

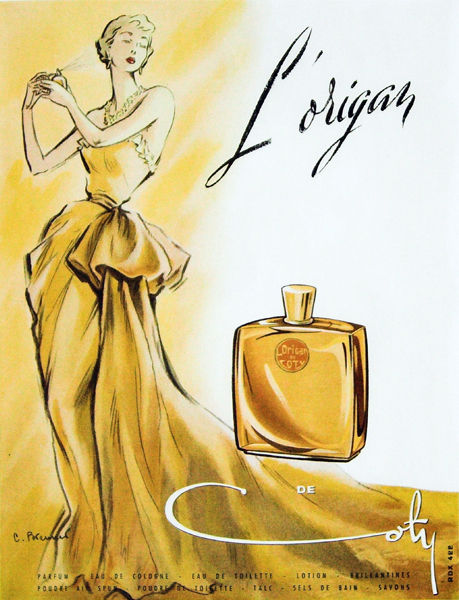

The turn of the century was a significant time in French perfumery. At the forefront was Francois Coty, the perfumer and entrepreneur who conquered the fragrance world. His success was immense. Perfume historian Michael Edwards explains, “Coty’s philosophy was simple but revolutionary. ‘Give a woman the best product you can make,’ he would say, ‘present it in a container of simple but impeccable taste, ask a reasonable price for it, and you will witness the birth of a business the size of which the world has never seen.’”3 Coty’s first major success was L’Origan in 1905. Coty used Firmenich’s new synthetic bases Iralia and Dianthene4 to modernise his classic perfume structure of citrus, flowers and woody notes, which included sandalwood. Without L’Origan, many other legendary perfumes would not have followed. It was a trailblazer that unfortunately did not endure into the millennium, but a faithful reconstruction of the formula can be smelled at the Osmothèque in Versailles, France.

Paris in the 1920s brought about new expressions in art, literature, music and fashion. Couturier Coco Chanel became the matriarch of French fashion and with her contemporaries Paul Poiret and Jeanne Lanvin, the concept of the designer fragrance became a standard followed to this day. Chanel No. 5 is still one of the most successful perfumes ever launched. The designer had enlisted the help of Russian-born perfumer Ernest Beaux, who had spent time in a military post near the Artic Circle during the First World War.

Beaux recalled the fresh scent of Artic lakes and rivers, which he recreated in a laboratory on his return to France. He used a blend of aliphatic aldehydes, which provide No. 5 with its delicate, sparkling signature. Chanel commissioned Beaux to create additional perfumes. Cuir de Russie was Beaux’s study of leather notes and Bois des Iles was his study of sandalwood. Launched in 1929 and available today as part of Chanel’s Les Exclusifs collection, Bois des Iles captured the mood of Paris in the Roaring Twenties. It was the Jazz Age, the era of Art Deco and Europe’s fascination with Orientalism only increased. Perfumes like Bois des Iles and Guerlain’s Shalimar were escapism to a romanticised version of life in the East. Sandalwood became an important ingredient used to convey this story in luxury fragrances.

As the decades progressed, mindsets towards fragrance shifted even though the use of sandalwood oil remained prolific. As a new millennium approached, trouble on the horizon was unavoidable. The supply of Indian sandalwood was finite, and no sustainable source was available. One of the last legendary fragrances of the 20th century to use sandalwood oil in excess was Guerlain’s Samsara, launched in 1989. A stunning fragrance by Jean-Paul Guerlain, referencing the wheel of life in ancient Sanskrit, Samsara was launched 100 years after the creation of Jicky two generations before. Guerlain created the fragrance for a friend who had never been able to find her perfect scent, but she knew she liked jasmine and sandalwood.

“The secret of Samsara is the work Jean-Paul did with sandalwood, it is a notoriously difficult material to work with as it plays tricks with your nose - one minute it is there, the next it has gone. It is paradoxical, as it has enormous tenacity and lingering quality, but it suppresses the materials that are used with it. It had never been used in huge dosage before; the first to try to push the levels was Ernest Beaux in Chanel's Bois des Iles; however, John-Paul pushed the levels from two percent to 30 percent of the structure and enhanced them with newly discovered sandalwood notes,”5 wrote Roja Dove who worked with Guerlain for many years. The new notes Dove mentioned were Polysantol from Firmenich and Sandalore from Givaudan. Their combination lightened the overdose of Indian sandalwood oil, giving it buoyancy and allowing the floral notes in the heart of the fragrance to shine.

For the following two decades as the global shortage of sandalwood reached crisis-level, and almost all fragrances relied solely on synthetic sandalwood replacers or native Australian sandalwood to achieve the note. It is only recently, since a sustainable resource of Santalum album has been established that creativity with sandalwood fragrances is again flourishing, which is the topic for another article.

1. Sanchez, T. (2008). ‘Bois des Iles (Chanel)’ in Turin, L. Sanchez, T. Perfumes The Guide. London, UK: Profile Books, pp. 101

2. Penhaligon’s. Hamman Bouquet. Retrieved March 15, 2021, from https://www.penhaligons.com/uk/en/product/hammam-bouquet-000000000065161332

3. Edwards, M. (2019). ‘L’Origan’ in Edwards, M. Perfume Legends II. Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France: Emphase, pp. 21

4. Dove, R. (2008). ‘The Great Classics’ in Dove, R. The Essence of Perfume. London, UK: Black Dog Publishing, pp. 91

5. Dove, R. (2008). ‘The Great Classics’ in Dove, R. The Essence of Perfume. London, UK: Black Dog Publishing, pp. 172-173